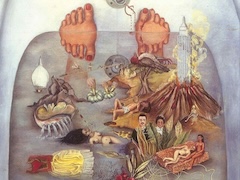

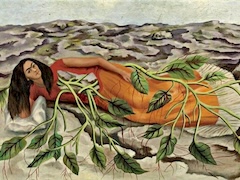

Self Portrait Along the Boarder Line Between Mexico and the United States

In Self Portrait Along the Boarder Line Between Mexico and the United States, the sun and moon hold sway only over Mexico, which was, this painting tells us, where Frida wanted to be. While Diego Rivera was busy eulogizing modern industry on the walls of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Frida was yearning for the ancient agrarian culture of Mexico. In her painting she is dressed up in an uncharacteristically sweet pink frock and lace gloves. But she herself is far from demure. As in her first self-portrait, her nipples show beneath her bodice. Her face is poised for mischief, and, again in defiance of propriety, she holds a cigarette. She also holds a small Mexican flag, which tells us where her loyalties lie.

Frida stands on a boundary stone that marks the border between Mexico and the United States. The stone is inscribed "Carmen Rivera painted her portrait in 1932." Perhaps she used her Christian name and her husband's last name as part of her pretense of being proper-she loved to shock Grosse Pointe dowagers by seeming to be shy and then coming out with off-color expressions delivered in slightly incorrect English to make it seem as if she didn't know what they meant. (In Spanish, too, Frida swore like a mariachi.) Or she could have used the name Carmen Rivera instead of her habitual Frida Kahlo because that is what the press called her in articles describing her as Rivera's petite wife who sometimes dabbled in paint. Rivera knew better - once in his awkward English, he introduced her to Detroit journalists by saying "His name is Carmen," and another time he called her "la pintora mas pintor," using both the feminine and masculine terms for painter in recognition of her strength and perhaps also of her androgynous nature. It is probable that he called her Carmen because he did not want to use the German name Frida during the rise of Nazism. For the same reason, about 1935 Frida herself would drop the e with which she had always spelled her name (Frieda).

In Self-Portrait on the Border Line a fire-spitting sun and a quarter moon are enclosed in cumulus clouds that, when they touch, create a bolt of lightning. By contrast, the single cloud over the United States is nothing but industrial smoke spewed from four chimney stacks labeled FORD. And instead of encompassing the sun and moon, the American cloud besmirches the American flag, whose artificial stars have none of the dazzle of Mexico's real sun and real moon. Whereas the Mexican side of the border has a partially ruined pre-Columbian temple, the United States has bleak skyscrapers. Whereas Mexico has a pile of rubble, a skull, and pre-Columbian fertility idols, the United States has a new factory with four chimneys that look like automatons. And whereas Mexico has exotic plants with white roots, the United States has three round machines with black electric cords. The machine nearest Frida has two cords. One connects with a Mexican lily's white roots, the other is plugged into the United States side of the border marker, which serves as Frida's pedestal. She, of course, is as motionless as a statue, which is what she pretends to be. With the high-voltage irony of her withering glance, Frida looks, once again, like a "ribbon around a bomb."