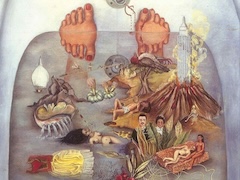

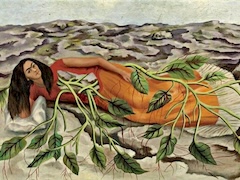

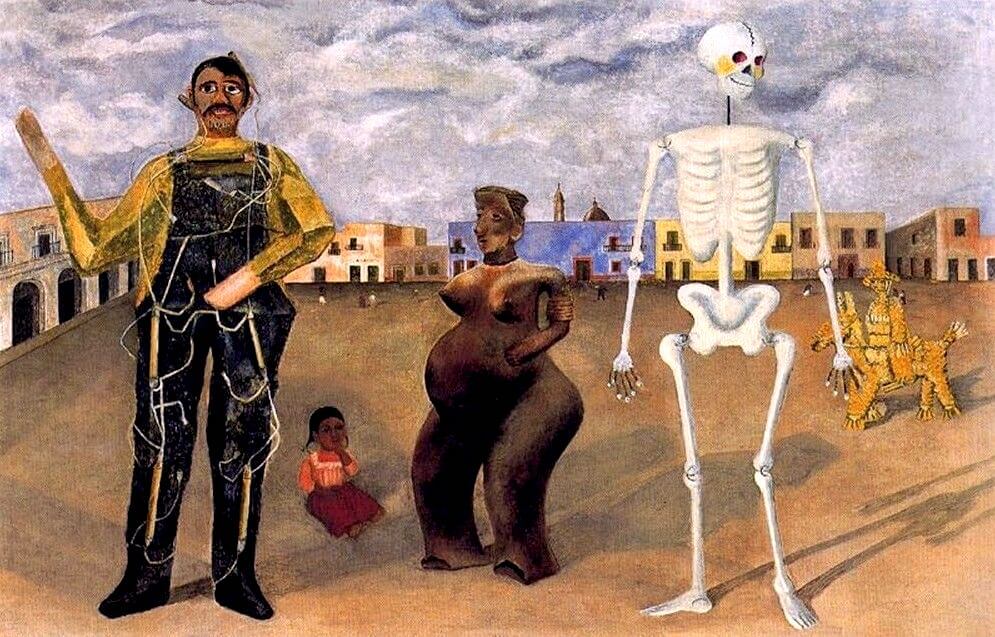

Four Inhabitants of Mexico, 1938 by Frida Kahlo

In Frida's self portrait at My Grandparents, My Parents, and Me, she was holding the ribbon of her family tree and was secured by the Blue House's patio walls. After two years when she painted herself at around age of four in Four Inhabitants of Mexico, she shifted her concentration from ancestral ties to the binds to her Mexican heritage, encapsulated in a cast of characters focused around antiquities that the Riveras claimed. This painting depicts four personalities, a Judas, a pre-Columbian symbol from Nayarit, a skeleton of the sort that kids like to dangle on the Day of the Dead, and a straw man riding a donkey.

In this painting, Frida takes herself as a young kid sitting on the ground sucking her inside finger and holding on to her skirt, She has a feeling of loss because her mother has let her sit without bothering her. She looks in amazement at the pregnant mud image; the skeleton, also, is in her line of vision. The image, with her broken and repaired head, addresses Mexico's past. Since the fronts of her feet are missing, we know she also stays for Frida, who had different foot operations in the 1930s, one of which (in 1934) incorporated the evacuation of parts of the toes of her right foot. Despite the sufficiency of the image, this mother figure is no more empowering than the medicinal guardian in My Nurse and I. Unquestionably, none of the four inhabitants of Mexico takes any notice of Frida. She is connected with them just by the plan of her shadow with theirs. The square's epic opening and the slant of estrangement must reflect the kid's vision. Four Inhabitants of Mexico is like an awful dream.

The risk of the Judas is made valid by an arrangement of circuits that covers him from head to foot. To Frida, regardless, he was an amusing figure: "It is expended," she said, ". . . it makes fuss, it is delightful and in light of the fact that it goes to pieces it has shade and structure." The Judas is the banality macho, the converse of the withdrew pregnant female. His shadow moves between the pregnant symbol's legs and lies on the earth by hers, interfacing them as a couple. His periphery and his blue overalls remember him with Diego Rivera, who at one point kept an about indistinct Judas next to his easel. These two "inhabitants" give a kind of make-acknowledge family for the child Frida, nonetheless they don't decrease her disconnection.